Why Do We Need Hurricanes on Planet Earth? The Ultimate Purpose and Benefits of Hurricanes By “Wayne Neely ”

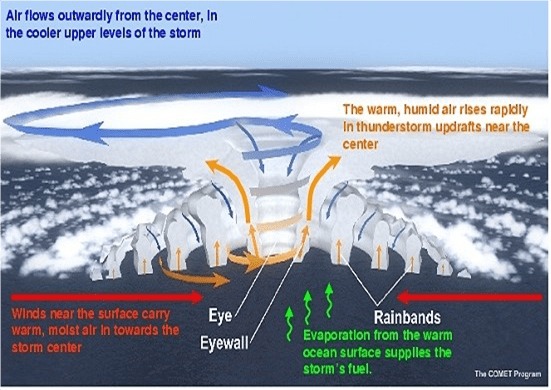

A cross-sectional view into the structure of a hurricane (Image courtesy of The Comet Program).

Dorian was the fourth named storm, second hurricane, the first major hurricane, and the first Category 5 hurricane of the 2019 North Atlantic hurricane season. Hurricane Dorian struck the island of Abaco at sustained wind speeds of 185 mph. Dorian went on to strike Grand Bahama at a similar intensity, stalling just north of the island with unrelenting winds and rainfall lasting for at least 24 hours. The resultant damage to these two islands was catastrophic; most structures were flattened or swept out to sea, and at least 70,000 people were left homeless. The estimated total cost of Dorian was $3.4 billion (2020 BSD), and even that is not the final total, and all indications are that this total will increase. Dorian also caused 74 deaths, and hundreds are still reported missing.

I mentioned Hurricane Dorian here because, after the passage of this storm, most media (local and international) and laypersons alike were all complaining about Dorian’s negative aspects without even mentioning one positive attribute about this hurricane many other past storms. The great devastation from these storms takes precedent over the good that they do. Today, it is fair to say meteorologists are beginning to believe that tropical cyclones may more than offset the damage they cause by the good they do. Scientists already know that in such places as The Bahamas, Caribbean, Central America, Japan, India, and Southeast Asia, and even in the south-eastern portion of the U.S.-Tropical storms and hurricanes provide up to 60% of available rainfall in any given year. Suppose man’s interference with such storms ever cut off this vital precipitation. In that case, the results could be ruinous for farmers and other agriculture based-businesses, manufacturing and other industries, and water-dependent sectors such as drinking-water supply companies.

If we crunch the numbers for a mature hurricane, it can release a massive amount of heat energy into the atmosphere at a rate upwards of 6×1014 watts or 5.2 x 1019 Joules/day! This released heat energy is equivalent to about 200 times the total electrical generating capacity on the planet. NASA says that “during its life cycle, a hurricane can expend as much energy as 10,000 nuclear bombs!” And we are just talking about an average hurricane here, not mega-storms like Hurricane Dorian. Moving along on the open sea causes large waves, heavy rain, and high winds, disrupting international shipping and, at times, causing shipwrecks. Generally, after its passage, a hurricane stirs up the ocean waters it traverses, lowering sea surface temperatures behind it. These cool temperatures wake can cause the region to be less favorable for a subsequent hurricane. On rare occasions, however, storms may do the opposite. For example, 2005’s Hurricane Dennis blew warm water behind it, contributing to the unprecedented intensity of Hurricane Emily, which followed it closely. Hurricanes help maintain the global heat balance by moving warm, moist tropical air to the mid-latitudes and polar regions and influencing ocean heat transport. Was it not for the movement of this heat poleward (through other means as well), the tropical regions would be unbearably hot and not sustain human life.

Although there is a lot of media coverage of the damage and destruction accompanying tropical storms and hurricanes, the most notable was Hurricane Dorian in 2019; such storms can also significantly benefit the areas they impact. Hurricane Dorian was an extremely powerful and devastating Category 5 North Atlantic hurricane that became the most intense tropical cyclone on record to strike The Bahamas and is regarded as one of the worst natural disasters in this country’s history. It was also one of the most powerful hurricanes recorded in the North Atlantic Ocean in terms of 1-minute sustained winds, with these winds peaking at 185 mph. Also, Dorian surpassed Hurricane Irma in 2017 to become the most powerful hurricane on record in the open North Atlantic region, outside of the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. Hurricanes also have positive effects such as:-

- Bacteria and red tide breakup.

- Help to balance global heat.

- Acts as the Earth’s filter system

- Replenishment of barrier islands.

- Replenish inland plant life.

- Replenish the underground aquifers.

- Spread plant seeds and spores.

- Provide valuable economic aid and growth to the hurricane-stricken regions.

Hurricanes are usually seen as terrible destructive forces of nature, but they are an integral part of nature. Life in the hurricane-prone areas has evolved to adapt to these great storms and benefits from them. Hurricanes and tropical storms can bring drought-busting rains. They can perform the same cleansing function as forest fires in a forest in maintaining the conditions needed for healthy coastal forests, particularly in swampy mangrove forests.

Landfalling hurricanes can be an essential source of water, water that can lessen droughts and recharge underground aquifers. This water would also be necessary for manufacturing industries highly dependent on water to manufacture their products, and many of these products may drive the local or country-wide economies. Each summer and fall, severe tropical cyclones, known as hurricanes, become a major meteorological peril for inhabitants of the Caribbean, The Bahamas, Latin America, and The United States Eastern and the Gulf Coast States. Hurricane Dorian was a compelling and devastating Category 5 North Atlantic hurricane that became the most intense tropical cyclone on record to strike The Bahamas. In addition, Dorian is regarded as one of the worst natural disasters in this country’s history. The storm surge and winds of hurricanes may be destructive to human-made structures. Still, they also stir up the waters of coastal estuaries, which are typically important fish-breeding locales.

The winds and waves of the hurricane can oxygenate the near-surface waters, and they help life to return to the areas where the outbreak of bacteria and red tide once existed. The cyclone can break up bacteria and red tide that lurks in the impacted water. As the tropical cyclones move across the ocean, the winds and the waves violently toss the water’s contents about the area and dissipating these deadly microscopic organisms within that area. The winds can oxygenate the near-surface waters, and they help life return to the places where the red tide or bacteria once existed. The winds can re-oxygenate the near-surface waters, and they help life return to the areas where the red tide or bacteria once existed. These events are especially noticeable along the US Gulf Coast States, especially along Florida’s west coast during the late hot summer months when bacteria and red tide are pretty recognizable and prevalent.

Hurricanes replenish inland plant life, and their winds blow the spores and seeds further inland from where they would typically fall. This increase in the redistribution of plant life can be seen a thousand miles inland as the storms move away from the shoreline. These seeds can replenish lost growth after forest fires and urbanization. Hurricanes perform this vital function of seeds and spores’ dispersal and play an essential and critical role in the ecology of the forest plants’ lives. Hurricanes may destroy organisms, but they may also promote their spread. Seeds and spores borne on their strong winds may be dispersed or propelled far from their sources, facilitating the dispersal of many plant species. In South Florida, tropical hardwood hammocks — patches of rich jungle scattered amid expanses of sawgrass meadows and pine forests – more than likely had helped from hurricanes. In The Bahamas, the Australian Pine seeds were more than likely spread throughout the islands by the powerful winds of past storms. However, there are other beneficial trees whose seeds were spread throughout The Bahamas and the Caribbean by hurricanes. Most of the shrubs and trees composing these shadowy, wild pockets consisting of West Indian mahoganies, gumbo-limbo, strangler fig, and others came from the Caribbean and the Central and South American tropics. While many of these seeds likely reached the southern tip of Florida and the Caribbean via bird gullets or ocean currents, scientists speculate that hurricanes churning in from the North Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico are also responsible for these transfers.

The strong winds from the hurricane can contribute to the agricultural sector in the long run. It can cause the topsoil of an area to be redistributed to the areas in which it was lacking. By the redevelopment of infrastructure, the property values and the living conditions in some areas will improve. The hurricane also helps to build up the coastal regions of the islands, making the islands wider. Habitat modifications are another beneficial effect of hurricanes. Intense rainfall of the tropical cyclones causes high soil runoffs, and it causes high sediment levels to be deposited in the estuaries threatened by rising sea levels. The hurricane storm surge carries substantial amounts of sediments and nutrients in the coastal marshes. The hurricane causes minor long-term damage to the wetlands. At the same time, foliage may be stripped, stimulation from new nutrients brought in by the hurricane and quickly returning the marshes to their original condition. Hurricanes can deposit vast quantities of seafloor and estuary sediments as they move ashore, accumulations that provide footholds for coastal vegetation communities. The hurricane may ravage existing mangrove swamps and mound-up banks of sand, mud, or marl – soil consisting of limestone and clay – in which seedlings or dislodged mature trees establish new stands. In hypersaline lagoons, such as the Laguna Madre complex of south-eastern Texas and adjoining Mexico, hurricanes periodically flush the salty waterways, providing notable contributions of more diluted seawater and freshwater rain and runoffs. Furthermore, hurricanes and tropical storms are usually seen as terrible destructive forces of nature. However, they are a critical part of nature, and life in hurricane-prone coastal areas have evolved to adapt to these great storms and even benefit from them. (Shaw 2018).

The strong winds from the hurricane can also contribute to the productivity within the agricultural sector in the long run. As we have seen, hurricanes can bring drought-ending rainfall. They play a vital or critical role in the environment and also perform the same vital cleansing function as forest fires in maintaining the conditions needed for healthy coastal forests, particularly in swampy mangrove forests. The intense rainfall of tropical cyclones causes high soil runoffs, resulting in high sediment levels being deposited in estuaries threatened by rising sea levels. Hurricane storm surges also transport substantial amounts of sediments and nutrients in coastal marshes. Studies show that hurricanes cause little long-term damage to marshes. While foliage may be stripped, the stimulation from new nutrients brought by the hurricane quickly returns the marshes to their original condition, benefiting most fishes, plants, and animals living within the mangrove ecosystems. It cannot be denied that hurricanes can negatively affect residents in their paths. But on a broader scale, ecosystems within their paths often evolved because of this influence and can benefit from a hurricane’s periodic beating. But for humans, hurricanes often exact a terrible price on life and property. (Masters 2005).

Ecological succession is a significant benefit that hurricanes bring to an area or region impacted by the storm. A hurricane that flattens a hardwood hammock or a deciduous forest may seem an agent of destruction. Still, such disturbances are a natural and necessary part of the forest ecosystem function. The toppling or defoliation of mature canopy trees during the passage of a hurricane, allows sunlight to reach the previously dark understory, allowing shade-intolerant species to proliferate. These may experience years of dominance until shade-tolerant trees create a canopy again. Such cycling of vegetation communities is called succession, and it promotes biodiversity by giving more species the chance to occupy a given ecosystem and maintaining landscape mosaics of greater complexity.

Hurricanes act as the Earth’s filter system by removing polluted and toxic air from the atmosphere and the environment. Without them, the atmosphere will get more toxic and eventually not support life on this planet. It seems inconceivable that something so large and deadly as a hurricane could have a beneficial side. The hurricane provides the ‘global heat balance’; one of the primary purposes for a hurricane or, better yet, tropical cyclones worldwide is the temperature balance between the poles and the equator. Tropical cyclones help transport heat energy from the equator towards the poles. The imbalance of temperatures will exist due to the orientation of the polar axis of our planet. Earth’s equator receives more solar energy, called insolation, than any other latitude. The insolation warms the ocean temperature that heats the air above it and keeps it warmer long into the autumn. The Earth is trying to spread or disperse this warmth energy around the world, and hurricanes are one of the handy ways this is accomplished; mid-latitude storm systems and oceanic currents are others. Hurricanes are very efficient movers of equatorial heat due to their size and interactions with the atmosphere’s upper levels. The equator would be progressively warmer, and the poles could be cooler if these tropical cyclones did not exist.

Hurricanes are very efficient movers of equatorial heat due to their size and interactions with the upper levels of the atmosphere. It is prominent that some of the lower latitude areas tend to see a hike in temperatures during a year, and the higher latitudes get a fall in temperatures. Hurricanes are just giant heat engines that pick-up warmth from the oceans in the warmer latitudes and transport it to colder locations, helping to balance the Earth’s warm and cold zones, often referred to as the Earth’s ‘global heat balance.’ The imbalance of Earth’s temperatures will exist due to the orientation of the polar axis of our planet. Earth’s equator receives more solar energy, called ‘the insolation’, than any other latitude on a yearly average. This insolation warms the ocean temperature, which in turn warms the air above it and keeps it warmer long into the autumn.

The Earth is always trying to spread heat energy worldwide, and hurricanes are one of the most efficient ways this movement is accomplished. Mid-latitude storm systems and ocean currents are other ways this is achieved. The insolation warms the ocean temperatures, which warms the air above it and keeps it warmer long into the autumn months. Tropical oceans have been soaking up the sun’s energy and heat since water first covered the Earth. Yet, the oceans have not gotten any warmer in a significant way. The warmest parts of the oceans generally stay below 32 degrees Celsius. Ocean currents and the weather in the atmosphere, including hurricanes, constantly work to equalize the Earth’s heat budget by redistributing this heat away from the tropics and poleward. As the water vapor rises from the sea, it cools, condenses, and releases enormous amounts of heat into the atmosphere. This heat, in turn, causes more evaporation and condensation, further fueling the brewing storm like the updraft in a chimney. On the other hand, cold fronts do the opposite by transferring cold polar air to the tropics.

As the winds build and the tropical storm moves away from the equator, it releases enormous amounts of heat called ‘latent heat of condensation.’ In a full-fledged hurricane, which has winds of 75 mph or more, there is as much energy released in a single day as by the detonation of 400 20-megaton hydrogen bombs. Hurricanes also help maintain global heat balance by moving warm, moist air from the tropics to the mid-latitudes and polar regions. Hurricanes can move massive amounts of heat, cooling the tropical waters and warming the air by releasing heat as they weaken while moving north. It is estimated that as much as one cubic mile of the Earth’s atmosphere is stirred up every second during a hurricane. Were it not for the movement of this heat polewards (through other means, such as ocean currents and global wind patterns), and the tropical regions would become unbearably hotter. The polar regions would become unbearably colder, and both areas would not support life on this planet. These hurricanes are responsible for maintaining a positive balance between the heat at the poles and the tropics.

Many meteorologists and other scientists are becoming even more convinced that tropical cyclones have an even more significant and less understood role. They may well be a crucial factor in maintaining the planet’s heat balance, which is essential to the well-being of all life here on this planet. During this process of transferring heat from the equator to the poles, hurricanes also perform the necessary function of cleaning the air of contaminants and pollutants found in the atmosphere. In addition, this function is also performed through other means, such as ocean currents and global wind patterns. Which would build up over time, and eventually, the Earth’s atmosphere would become too toxic from these contaminants and pollutants to support life. The other big heat distributors on the planet are ocean currents-such as the Gulf Stream-that move perhaps as much as a third to a half of the equator’s excess heat toward the poles.

The atmosphere and oceans are entwined, each constantly affecting the other. Oceanographers and meteorologists use the term a ‘coupled system’ to describe the interaction of two of the dominant factors of the Earth’s climate. It is a system that distributes heat in three dimensions. Everywhere, when warm air is rising, cooler air is being pulled in to replace the rising warm air. Similarly, cool water surfaces in the oceans replace warmer water driven by winds along the surface. Hurricanes, ocean currents, and global wind patterns play a critical role in distributing heat within the Earth’s atmosphere and the oceans. Without them, this complex and dynamic heat distribution system and redistribution as we know it will not exist. Perhaps as much as a third to a half of this heat is distributed by the ocean currents. The movement of the atmosphere transports the rest. A large portion of this atmospheric heat-the exact percentage is unknown-is picked up from the sea by hurricanes.

Such tremendous energy released by hurricanes gives them their purpose in life. In the global atmospheric ecosystem, the primary function of all these storms is to equalize the great heat imbalance that builds up between the equator and the poles. At higher latitudes, it is the familiar mid-latitude cyclones or frontal systems that do the job. In the tropics, hurricanes are particularly very efficient at transferring heat from the equator to the poles. They extract latent heat from the oceans, convert them to sensible heat, and lift it to the upper atmosphere, from where the heat energy is transferred poleward. Most hurricanes tend to die out when they encounter cold water because cold water evaporates less readily than warm water and, without a continuous supply of moisture-rich water vapor, hurricanes soon ‘run out of steam and die.’

In addition, some hurricanes are deprived of their needed vapor supply when they pass over a land area or cooler waters, but the effect is the same-Death. What would happen if a man ever interfered drastically with this process? Meteorologist says that it could result in some frightening or dire consequences. Unable to shake off their heat, the tropics might become warmer and warmer. Simultaneously, the polar regions would slowly become colder. Eventually, both areas would expand, relentlessly shrinking the densely populated temperate zones between them. Suppose man’s new technology ever prevented them from releasing their heat through tropical cyclones. In that case, the tropical seas might warm up until this tremendous amount of stored heat would be released in the form of super hurricanes that could make their present-day counterparts seem as mild as a summer downpour.

While tropical cyclones may seriously damage countries, destruction encourages rebuilding. For example, the devastation wrought by Hurricane Camille in 1969 on the Gulf Coast spurred redevelopment, significantly increasing local property values. Research indicates that the typical hurricane strike raises real estate house prices by a few percent for several years, with a maximum effect of 3 percent to 4 percent three years after their occurrence. However, disaster response officials point out that redevelopment encourages more people to live in clearly dangerous areas subject to future deadly storms. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 is the most obvious example, as it devastated the region that had been revitalized after Hurricane Camille. Many former residents and businesses do relocate to inland areas away from the threat of future hurricanes.

Hurricanes also have significant archaeological benefits. The strength of storms has benefitted archaeologists by unearthing downed airplanes, shipwrecks, and other historical relics in tidal locations where debris, silt, and sand, are washed away by the storm surge. For example, Hurricane Isaac exposed the fragments of The Rachel in 2012. The Rachel was a schooner built in the course of the First World War. A hurricane struck the east coast of Florida, sinking 10 Spanish treasure ships and killing nearly 1,000 people on July 31, 1715. All of the gold and silver on board of the ships at the time would not be recovered until 250 years later, when another hurricane unearthed it.

Christopher Columbus crew member Vicente Yáñez Pinzón lost two ships with their crews near Xumeto (Jumeto) or Saometo, called by Columbus “La Isabela,” or what we now know as ‘Crooked Island’ in The Bahamas. His other two vessels sustained damage but escaped to Hispaniola for repairs. The Vicente Yáñez Pinzón is the first hurricane known in The Bahamas and probably Florida as well. Vincent Pinzon (Commander of the ship Nina during Columbus’ first voyage to the New World) had just come from discovering Brazil, crossed the Gulf of Paria, and continued sailing onto the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico until he found himself in The Bahamas. It was there that he lost two of his ships ( Pinta and Frailia) and two others badly damaged when they were dashed against some rocks in the vicinity of Crooked Island.” In September of 1500, he went back to Palos in Spain after suffering the loss of two of his ships. In late July of 1500, Pinzón’s good luck finally ran out, as the Pinta was lost, caught in a hurricane while anchored near Crooked Island in The Bahamas and near the Turks and Caicos Islands. She sank, fully loaded with gold and jewels, along with another ship, the Frailia. Suffering the loss of many men and now with only two somewhat battered ships remaining, Pinzón managed to barely make it back to Palos, in Spain, arriving there in October.

In March 1980, treasure hunters Mr. Olin Frick and Mr. John Gasque located what they believed to be the wreck of the Frailia, the second ship that sank. Later they returned and removed two cannonballs, which turned out to be made of solid lead. The discovery of these lead balls dated the wreck before 1550. After this time, the manufacture of cannonballs with both iron and lead together was used. These two treasure hunters claimed to have found the Pinta, one of three ships Christopher Columbus sailed to the New World in 1492. They hoped to raise the vessel from its watery grave on a tropical reef and bring the remains to the United States for display. Olin Frick and John Gasque, president, and vice-president, respectively, of Caribbean Ventures, Inc., first located the shipwreck in 1977 in 30 feet of water near The Bahamas on the West Caicos Bank, about 125 miles off the northern coast of Haiti. Based on the archeological opinions and 15th-century historical records, they felt sure that the sunken wreck was that of the Pinta, believed to have gone down in a hurricane in July 1500, while on another New World expedition. The following year, Gasque returned to the site and discovered another shipwreck that reportedly fits the description of the Pinta’s sister ship Frailia which also went down in the same hurricane. Both ships were initially unearthed during the passage of several storms over the area.

Other great economic benefits are gained from hurricanes. After a storm has devastated an area, it is often followed by a substantial infusion of insurance money and monies distributed from various charities and the private sector. As this money is spent, it tends to flow throughout the communities or country impacted and reinvigorates the community or country for years to follow. These monies spent often benefit people such as building contractors, plumbers, electricians, roofing contractors, plywood, drywall and window manufacturers, and other tradespeople. The hurricane often provides a blessing in disguise because, after the storm’s passage, there is often a drastic drop in the unemployment rate due to all these short and long-term jobs created.

Although natural disasters spread destruction and economic pain to a wide variety of businesses, for some, it can mean a surge in economic activity and revenue. For that reason, economists tallying the numbers expect the hurricanes will be neutral in their effect on the local economies or may even give it a slight boost, particularly because of an expected reconstruction boom in the already red-hot construction industry. For example, in Florida, the state hit hardest by the 2004-2005 storms, 20,000 jobs were created that otherwise would not have been if it were not for these storms. This much-needed aid provides a tremendous benefit to the community by helping them on the road to recovery. For example, when Hurricane Gilbert came ashore on the Caribbean island of Jamaica in 1988 and Andrew over The Bahamas in 1992, Gilbert brought Jamaica’s economy and the tourism industry to a virtual standstill for about 2-5 years. For Andrew in 1992, monetary-wise, $250 million was spent to get the country back to a state of normalcy post-Andrew. In 2019, Dorian had an even more significant impact on the economy of The Bahamas. Local and international aid flow within these countries helped significantly restore the countries’ economies on solid footing. Had it not been for this aid, some experts predicted that it would have taken Jamaica over seven to twelve years to recover from this storm and a similar amount of time for The Bahamas.

After seeing the violence with which nature releases its pressure valve in the form of hurricanes, one can understand the great need of nature to have some way to vent or release this abundant energy upon the Earth. Tropical cyclones are necessary to bring much-needed rainfall to areas along the coastal locales in the North Atlantic and replenish the groundwater supply. In other words, they recharge underground aquifers. The often-torrential rain associated with hurricanes can be a double-edged sword. Flooding is commonplace in the wake of a storm, threatening human life and property. But the deluges of passing hurricanes and their weakening but still wet remnants can also be a boon for areas experiencing the late-summer droughts that sometimes coincide with the tropical-cyclone season. Storm precipitation may benefit parched crops in a severely dry stretch of the growing season or help douse long-raging wildfires.

Tropical cyclones are incredibly efficient at rainfall production, and thus, can also be efficient drought busters. Although tropical cyclones take an enormous toll on lives and personal property, they may be important factors in the precipitation regimes of places they impact and bring much-needed precipitation to otherwise dry regions. Past hurricanes have often been responsible for breaking droughts. Cyclones in the Pacific usually supply moisture to the southwestern United States and parts of Mexico. Japan receives over half of its rainfall from typhoons, and India gets 75% of its precipitation from tropical cyclones. Hurricane Camille in 1969 averted drought conditions and ended water deficits along much of its path, killing 259 people and causing $9.14 billion in damage to Mississippi and Virginia. Another example, a severe drought in Texas was ended by the rains from Hurricane Allen and Tropical Storm Danielle in the summer of 1980.

On a worldwide scale, the occurrence of tropical cyclones can cause tremendous variability in rainfall over the areas they affect. Indeed, these tropical cyclones are the primary cause of the most extreme rainfall variability, as observed in places such as Onslow and Port Hedland in subtropical Australia, where the annual rainfall can range from practically nothing with no cyclones to over 1,000 millimeters (39 in) if storms are abundant. After the Great Andros Island Hurricane of 1929, Hurricane Floyd in 1999, and Hurricane Michelle in 2001, all three systems ended short periods of drought or lower than average rainfall over The Bahamas during these respective years. For example, The Bahamas experiences a tropical climate with a dry and wet season but no distinct cold season. The wet season occurs from May to October, with the dry months lasting from November to April. June is the month when the rainfall over The Bahamas is at its peak, with August being the next wettest month. The wet season also coincides with the North Atlantic hurricane season and ends mid to late October with the winding down of the hurricane season. In Nassau, here in The Bahamas, at the Lynden Pindling International Airport, the average annual rainfall is 56.27 inches. Of that total, 38.9 inches falls during the hurricane season (approximately 70% of the total). A greater proportion of this total is from hurricane-related systems such as tropical disturbances, tropical waves, tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes (these totals are slightly higher in Grand Bahama and somewhat lower in Inagua). Could you imagine the problems we would face as a country if we did not have tropical systems here in The Bahamas? Other islands in the Caribbean also have similar rainfall patterns with hurricanes, just like The Bahamas. In the coastal areas of the United States, many industries, such as ranching and agriculture, are dependent on vital water resources from hurricanes.

Another vital benefit of tropical storms and hurricanes is that these storms often flush pollutants from rivers, lakes, coastal shorelines, and bays. Hurricanes have the power to pick up the substantial amounts of sand, nutrients, and sediment on the ocean’s bottom and bring them toward those barrier islands. The storm surge, the wind, and waves will move these islands closer to the mainland as the sand is pushed or pulled in that direction. Sand is carried from the continental shelf to the beaches. These are the natural benefits of tropical cyclones. Hurricanes of various kinds are as much a depositional event as an erosional event. Much attention is given to the destructive aspects of major storms because of the loss of life and property, but little is known about their beneficial effects on coastal accretion.

The storm surge and the powerful winds of hurricanes may be destructive to human-made structures. Still, they also stir up the waters of coastal estuaries, which are typically important fish breeding locales. The tropical cyclones cycle the nutrients from the seafloor of the ocean to the surface by stirring the sea, boosting ocean productivity, and setting the stage for marine life blooms. By raising nutrients from the seafloor to surface layers of the ocean, hurricanes also increase biological activity in areas where life would be difficult through nutrient loss in the deeper reaches of the sea. Marshes can benefit from the effects of hurricanes and related weather systems. First, hurricanes typically increase precipitation in regional areas. This added rainfall increases critically eroded sediment runoff into the sea, rivers, lakes, and bayous. As these water pathways overflow their banks, they deposit the extra sediment in marsh and wetland areas, encouraging wetlands growth. Second, they usually stir up the ocean and give rise to a widely known process as the upwelling. This process is an integral part of the thermohaline circulation which can be seen as one more critical mechanism responsible for transferring heat from the tropics to the poles and thus maintaining a sustainable temperature at both locations. Hurricanes could be good for marine life too. Since they stir the ocean, the minerals on the bottom are mixed up, thus enhancing the ocean’s productivity.

The fragile barrier islands need hurricanes for their survival, especially when the sea levels are rising. This dynamic process keeps the barrier islands alive. Hurricanes have the power to pick up the substantial amounts of sand, nutrients, and sediment on the ocean’s bottom and bring them toward those coastal landmasses and barrier islands. The storm surge, the wind, and waves will move these landmasses or islands closer to the mainland as the sand is pushed or pulled in that direction. Without the tropical cyclones or the artificial restoration, the barrier islands would shrink and sink into the ocean. Hurricanes can do immense barrier island damage, but they can bring some beneficial sand to the coastal areas.

While we can usually measure and map the instantaneous effects of a hurricane, we can only speculate about the long-term beneficial effects. Along with their massive destructive force, hurricanes can have beneficial effects as part of the rhythm of nature. Storms that erode beaches, uproot trees, and flatten wildlife habitats may also refresh waterways, revive dry areas, and bulk up barrier islands with redistributed sand. For example, The US National Park Service Incident Management Team also reported that wave erosion from Hurricane Dorian reshaped parts of the barrier islands in the Outer Banks in the Carolinas. What hurricanes do is help the environment by renewing coastal areas. Hurricanes help wetland areas such as the Florida Everglades, which was already undergoing an $8.4 billion environmental restoration until recently.

Hurricanes are a vital part of the natural processes that take place within the Earth. Hurricanes may serve as a flushing-out mechanism in areas such as in the Florida Everglades and Louisiana Bayous, where sediments have accumulated on the bottom of these waterways. Hurricanes may also help to eliminate some invasive exotic plants in the Caribbean and North America, such as Australian pines. On the other hand, they could also end up helping others if high wind disperses seeds to new places. The storm’s changes can also affect animal life. Beach mice in Florida’s Panhandle become easy targets for predators in flattened areas. But new dunes brought about by hurricanes also shield beaches from lights that confuse sea turtles when they come ashore to lay eggs and their babies after hatching.

When tropical cyclones cross land, thin layers of calcium carbonate of ‘light’ composition (i.e., the unusual isotopic ratio of Oxygen-18 and Oxygen-16) are deposited onto stalagmites in limestone caves up to 190 miles from the hurricane’s path. As the cloud tops of hurricanes are high and cold, and their air is humid – their rainwater is ‘lighter.’ In other words, the rainfall contains significantly higher quantities of unevaporated Oxygen-18 than other tropical rainfall, such as an afternoon thunderstorm. The isotopically lighter rainwater soaks into the ground, percolates down into caves. Within a couple of weeks, Oxygen-18 transfers from the water into calcium carbonate before depositing in thin layers ‘rings’ within stalagmites. A succession of such events created within stalagmites maintains a record of cyclones tracking within a 190 miles radius of caves going back centuries, millennia, or even millions of years.

At the Actun Tunichil Muknal cave in central Belize, researchers drilling stalagmites with a computer-controlled dental drill accurately identified and verified evidence of isotopically light rainfall for 11 tropical cyclones occurring over 23 years (1978–2001). Furthermore, they used this technology to discover past hurricanes going back to the 13th and 14th centuries that were previously undocumented. Five to six major hurricanes were observed in the sedimentary and cave records of the past 500 years along the central coast of Belize. This represents 1 to 1.2 catastrophic storms every 100 years in the study area. One giant hurricane struck the central coast of Belize sometime before AD 1500. Compared with Hurricane Hattie (Category 4) in 1961, which devastated Belize, this hurricane was significantly more powerful and capable of achieving catastrophic effects. Several other events appear to have been roughly equivalent to Hurricane Hattie. This study suggested that over the past 500 years, major hurricanes have struck the Belize coast on average once every decade. One giant hurricane with probably particularly catastrophic consequences hit Belize sometime before AD 1500. Temporal clustering of hurricanes suggests two periods of hyperactivity between 4500 and 2500 14C year BP, which supports a regional model of latitudinal migration of hurricane strike zones. The preliminary hurricane data, including the extreme apparent size of the giant event, suggest that prehistoric hurricanes were capable of having exerted significant environmental stress in

Maya antiquity. (McCloskey 2008). Worldwide, at the Chillagoe limestone caves in northeast Australia 81 miles inland from Cairns) researchers identified and matched evidence of isotopically light rainfall with 100 years of cyclone records. This study has created a catalog of tropical cyclones from 2004 back to 1200 A.D. (an 800-year record).

Hurricanes also affect the geomorphology of an area positively. From a purely natural standpoint, hurricanes are a blessing for coastal islands of the Caribbean, Bahamas, and North America, even though they are a curse for people who live there. Hurricanes reshape the geology near the coast by eroding sand from the beach and offshore, rearranging coral, and changing dune configuration onshore. Their rainwater gets absorbed into stalagmites within caves, creating a record of past hurricane impacts. Barrier islands like the Carolinas and low-lying coastal islands like The Bahamas need hurricanes for their survival, especially at times of rising sea levels. It is during hurricanes that these islands get higher and more expansive. Hurricanes could be good for these barrier and low-lying islands, mainly fragile islands that anyone could assume to get destroyed in such conditions. However, hurricanes are an essential part if they are to withstand even the rising sea levels. Hurricanes usually erode the beaches on the side of the oceans, but they also make up the other side by depositing new sediments due to winds. This dynamic process keeps the barrier and low-lying islands alive and not succumbing to the rising sea levels.

It is pretty easy to see why archipelagoes like The Bahamas and barrier islands in North and South Carolinas benefit from hurricanes. These are features that evolve and migrate, and hurricane furnishes the sand to do this. Without storms or hurricanes, there would probably be no migration. Therefore, these hurricanes widen the islands by over washing sand to the backside of the island, depositing it in the lagoon, and widening the island during this process. The U.S. National Park Service Incident Management Team reported that wave erosion from Hurricane Dorian in 2019 reshaped parts of the barrier islands in the Outer Banks of the Carolinas. However, the beneficial impact of hurricanes on islands such as in The Bahamas may be unique. Most environmentalists look at it because nature has always adjusted to its environment, and if hurricanes are there, the plants and animals are ready to adapt. Along the shore, the transport of sand, which occurs mainly during storms, can cause erosion at some spots and beach buildup at others, depending on the angle from which the waves approach. Even as hurricanes erode the oceanside beaches, their powerful winds and waves often deposit more sand onto the backside of islands, such as in The Bahamas or the Carolinas. If you do not let this periodic over wash happen, the islands get skinnier and skinnier and might disappear beneath rising sea levels.

Although hurricanes are destructive, in the long run, they can also have positive effects. Hurricanes offer us a chance to reflect on our place in nature. The incredible destructive power of hurricanes reminds us to be humble and realize that our capabilities are insignificant compared with the forces of nature. We should learn to try and co-exist with nature instead of trying to subdue it. As with hurricanes, it always seems as if nature will go back into a balance, and it will just not be what humans are used to experiencing on such a large scale. Humans do not like change. Nature does not mind; it just balances itself out.